I first learned about the significance of 'Beaumont Hamel' while watching military historian Gwynne Dyer's National Film Board series 'War'.

The St. John's Newfoundland native walked across today's soft

green fields of the Beaumont Hamel memorial park, and the reason for

Newfoundland's memorial observance each July 1 became apparent.

This British commanded advance was part of the opening of the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916.

It was to be a 'breakthrough' ... elusive in trench warfare ... so its

opening hours emphasized determined, courageous attack along a wide

front. As Dyer walked across a broad open field, he quoted reports of

the Newfoundlanders instinctively walking with their chins tucked into their chests as if

into the teeth of an Atlantic blizzard.

|

| Gwynne Dyer, during the 'War' years |

In his 1985 companion book to the series, Dyer includes a recollection from the beginning of the Battle of the Somme by author Henry Williamson. At 19 years of age in 1916, Williamson was a second lieutenant with the Bedfordshires. With just a few details altered, it could describe exactly what happened to the Newfoundland Regiment at Beaumont Hamel.

... the ruddy clouds of brick-dust hang over the shelled villages by day and at night the eastern horizon roars and bubbles with light. And everywhere in these desolate places I see the faces and figures of enslaved men, the marching columns pearl-hued with chalky dust on the sweat of their heavy drab clothes; the files of carrying parties laden and staggering in the flickering moonlight of gunfire; the "waves" of assaulting troops lying silent and pale on the tapelines of the jumping-off places.

I crouch with them while the steel glacier rushing by just overhead scrapes away every syllable, every fragment of a message bawled in my ear ... I go forward with them ... up and down across ground like a huge ruined honeycomb, and my wave melts away, and the second wave comes up, and also melts away, and then the third wave merges into the ruins of the first and second, and after a while the fourth blunders into the remnants of the others, and we begin to run forward to catch up with the barrage, gasping and sweating, in bunches, anyhow, every bit of the months of drill and rehearsal forgotten.

We come to wire that is uncut, and beyond we see grey coal-scuttle helmets bobbing about, ... and the loud crackling of machine-guns changes as to a screeching of steam being blown off by a hundred engines, and soon no one is left standing. An hour later our guns are "back on the first objective," and the brigade, with all its hopes and beliefs, has found its grave on those northern slopes of the Somme battlefield.

Gander, Newfoundland 1988

On the evening of July 28 1988, we were taking in the sights at Gander Airport. We watched assorted exotic birds come and go - remember the Cold War was still on but Cuba-bound communist nation aircraft needed refueling, too.

An older gentleman approached us, struck up a conversation, and explained he was waiting for one of his family members to fly in a Long Ranger helicopter. He was a little surprised by my instant, intense reaction to one element of his life story ... and my immediate request to shake his hand. For me, it was a priceless encounter with living history.

A couple of years ago, I was glad to notice his name as a contributor to an oral history project of Memorial University. Back in 1988, I was 'too polite' to request his photograph, but given the interest of the strange tourist 'from away', he surely would have agreed.

|

| That evening at Gander Airport in 1988. |

He was Hubert Miles ... and he had been at Beaumont Hamel ... as a replacement as he later explained. At 88 years old, he said he was one of the last two surviving Newfoundland World War One veterans and he had also revisited Beaumont Hamel in recent years with the Canadian Legion. He originally went over in July 1917. Specialized as a Lewis gunner, he had fought at Ypres, Cambrai and Montreuil ... if my later Holiday Inn notes are accurate. Wounded, he then worked as a stretcher bearer for a while.

Unrecorded in my notes is a story he told us of a gas shell landing nearby. (Whereas wind could quickly shift the poison gas plume venting from pressurized cylinders, gas shells delivered a smaller dose exactly where you wanted it - behind the enemy's lines) The concussion from the shell knocked him out briefly, and threw him into a water-filled shell hole. He had not been wearing his gas mask. However, he had been chewing a plug of tobacco. He credited the tobacco with saving him from the gas. He said when he came to and expectorated the plug, it had completely turned green. His amazement at this still came through 70 years later.

Eventually the helicopter arrived, we spoke briefly with the pilot, and we went our separate ways.

A few quick details about the British Army and the Newfoundland Regiment

British Army Organization

| Formation |

Commander |

Strength |

| Army | general | 200,000 |

| Corps | lieutenant general | 50,000 |

| Division | major general | 12,000 |

| Brigade | brigadier general | 4,000 |

| Regiment | colonel | 2,000 |

| Battalion | lieutenant colonel or major |

1,000 |

| Company | captain | 250 |

| Platoon | second lieutenant | 60 |

| Section | lance corporal | 15 |

- During war, these British formations would seldom have been at full strength during battle due to casualties.

- The larger a formation became, the more support personnel it would need for physical support, planning and administration.

- A battalion was the modern fundamental unit of battle ... with regiments being more of a 'traditional formation'.

- In Canada, an infantry 'regiment' was a parent organization which raised one or more battalions for service.

- Generally, during the Great War, soldiers seldom knew whose brigade, division, corps or army they were in ... as these often shifted around above their heads.

- As you already know ... in war, the strongest human bonds and loyalties are usually between soldiers in the same section or platoon.

However ... the 29th Division developed a reputation for determined fighting. As part of the 29th, and being the only representatives of Newfoundland ... there must have been an unusually strong cohesion among members of the Newfoundland Regiment. I have read that much of the first contingent came from the prominent families of St. John's - those who most clearly saw their interests being aligned with the British Empire.

And then there were all those great 'vacation' trips they took together ...

According to Martin Gilbert's book The Battle of the Somme (2006), between its being raised in Newfoundland ... and fighting at Beaumont Hamel ... the Newfoundland Regiment travelled as shown below.

The Newfoundland Regiment's location ...

| Date | Location |

| 1914 Oct 04 | St. John's, Newfoundland |

| 1914 Oct 14 | Devonport, England |

| 1914 Oct 21 | Bustard Camp |

| 1915 Feb 19 | Edinburgh |

| 1915 May 11 | Stobs Camp |

| 1915 Aug 02 | Ayr |

| 1915 Aug 20 | Devonport, for Mediterranean Sea |

| 1915 Aug 25 | Valetta, on Malta |

| Alexandria, Egypt | |

| 1915 Sep 20 | Arrive Gallipoli Peninsula |

| 1916 Jan 09 | Leave Gallipoli Peninsula |

| 1916 Mar 14 | Alexandria |

| 1916 Mar 22 | Marseille, France north thru France by rail |

| 1916 Mar 25 | Pont-Remy |

| 1916 Apr 04 | Louvencourt |

| 1916 Apr 22 | near Beaumont Hamel |

| 1916 Jul 01 | Beaumont Hamel advance |

The dates above may differ slightly from the accounts below. The purpose of the chart above is to give you a quick overview and framework on which to hang the interesting detail below.

The order of the published accounts is rearranged to provide a chronological account of the Regiment's experiences ...up to and including Beaumont Hamel.

The Regiment rebuilt and fought after Beaumont Hamel, being disbanded in 1919.

An account of the early experiences of the Newfoundland Regiment, published in December 1916 ...

Notes on the Newfoundland Regiment

'As we approach the end of another year, we give a short account of the work our Regiment has gone through since the war started.

'No attempt has been made to chronicle the doings of the Regiment, but we hope this will be undertaken in a thorough way so that authentic records, in a readable manner, will be handed down of what Newfoundlanders have done in the Great War.

'Our first contingent A and B Companies left St. John's October 4th, 1914, on s.s. Florizel, and met the Canadian contingent off Cape Race, and all proceeded together protected by British Men of War till they arrived at Plymouth.

|

| St. John's HarbourYou can almost smell the cod drying in the foreground. |

'Our boys were in tents on Salisbury Plains for several weeks, then they went to the permanent quarters of the Seaforth Highlanders at Fort George, Inverness, from there they were transferred to Edinburgh Castle.

'Our second contingent, Company C, left St. John's February 5th by s.s. Neptune, and boarded the s.s. Dominion off Bay Bulls for Liverpool They met the first two companies in Edinburgh Castle at which place they had just arrived. After about three months in Edinburgh they went to Stob's Camp near Hawick, and continued their drill for another three months.

'The first Battalion was then made up for Active Service, they reached Aldershot August 2nd, 1915, and were in the Badajos and Wellington Barracks for two weeks. During this time the King, Queen and Princess Mary visited Aldershot for inspection of the troops - the overseas Regiments forming the Guard of Honour. Lord Kitchener was here for this Review and when passing the Newfoundland Regiment, the boys heard him tell the Colonel: "You will have to get their bayonets sharpened as we have decided to send them to the Dardanelles." This was the first authentic information that the Regiment had of where they would be fighting. August 18th they left for Devonport where they boarded the s.s. Megantic. She went to Mudros, but was ordered back to Alexandria, as the Regiment required a new outfit suitable for this climate.

|

| Cairo souvenir postcard from 'the past'. |

'They remained at Cairo for eleven days. September 14th they left by s.s. Totona for Lemnos and thence by river boat to Suvla Bay, landing there on Sunday the 19th September getting their baptism of fire. Several were wounded in the landing. The Regiment went into the trenches at once, forming part of the famous 29th Division.

Suvla Bay at sunset |

'Very hard fighting had occurred when the Anzac and other Regiments were landing, and heavy casualties occurred in the endeavour to gain positions on the Peninsula overlooking the Forts on the Dardanelles, so that the Newfoundlanders went right into active service of the most critical kind.

'The place of landing was a beach about half a mile wide, and in the rear high hills rising five hundred feet or more with very little vegetation except prickly shrubs.

'The trenches were three to four miles from the beach and the routine work at first was four days in the trenches and then eight days rest in dug-outs near the Beach, but very soon from casualties and sickness the routine was eight days in the trenches and four days in the dug-outs.

'The path from the dug-outs to the trenches was through ravines and then a continuous connection of trenches to the front. In many places these trenches were exposed to an enfilading fire from prominent Turkish positions. The worst spot was a ridge afterwards known as Caribou Hill, where many engagements had taken place. This Hill was eventually captured by a small Company of Newfoundlanders in charge of Capt. Donnelly who held it, in spite of counter attacks, for forty-eight hours, until they secured reinforcements. The place was such a dangerous one that the Commander in charge believed the Newfoundland boys had been wiped out, until Donnelly himself brought the news, after dark, that they were hiding behind rocks and still held the Post. For this exploit he won the Military Cross and two of his men, Hynes and Greene, gained the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

'Caribou Hill had been a hornets nest for Turkish snipers and it was the greatest relief to the whole Division when this spot was captured. It went by the name of Donnelly's Post, and being on the crest of a solid rock the only protection was sand bags.

'The trying climate of severe heat during the day, followed by cold chilly nights, had a serious effect on the health of all, more especially as the only rest obtainable was in damp, cold, mud dug-outs. The need of good water and suitable food told heavily. Out of eleven hundred hardy, healthy Newfoundlanders, who landed on 19th September, only one hundred and seventy-two men were there to answer the Roll Call when the evacuation of the Peninsula occurred on 19th December. The whole expedition had been a list of troubles from the beginning, but the evacuation without any loss of life was one of the master strokes of the war.

[One Turkish account suggested they didn't fire

because they were simply relieved and happy to see the back of the invaders]

because they were simply relieved and happy to see the back of the invaders]

'To the remnant of the Newfoundland Regiment was given the honor of guarding the rear, and they were last to leave Suvla Bay. From there they went to Imbros Island, but after a few days were landed at Cape Helles to assist in the evacuation of that quarter. They proved just as successful here as in Suvla Bay, and on January 18, 1916, they arrived at Alexandria. They remained in Egypt guarding the Suez Canal till March 14th, when they were ordered to France and took up their quarters in the Arras District.'

This account of Beaumont Hamel was published circa October 1916

Better than the Best: Newfoundlanders in Picardy

'New and inspiring honours have been won by our troops in the fighting in France. It is generally known that the Newfoundland Regiment received its baptism of fire in Gallipoli, where it greatly distinguished itself in the battle for Caribou Hill.'When the British decided to withdraw from the Dardanelles the Newfoundland Regiment, and the troops of the 29th Division with which our Regiment has been brigaded since it took the field, were transferred to the front in France, and were almost immediately afterwards sent into the trenches in Picardy. At the end of June some companies of our men made successful sorties at night into the German trenches, seeking information or destroying the enemy's wire entanglements. But on July 1st at the commencement of the British offensive between the Ancre and Somme they were assigned much more important work, which they did so bravely that all the world applauded them, and the General commanding the 29th Division, Sir A. Hunter-Weston when thanking our men, said: "Newfoundlanders, I salute you individually. You have done better than the best." That was extraordinary praise for comparatively new troops to receive after their most important battle.

'The engagement of July 1st took place near the French village of Beaumont Hamel, south-east from the city of Amiens and due north of Albert. The way was paved for our men, firstly by an extensive artillery fire, and then by the advance of English regiments.The attack by our men on the German trenches, took place on Saturday, July 1st about 9 a.m. They were stationed in St. John's Road, at the right of Beaumont Hamel. They had been in their own trenches up to that time, in the third line defence, about 400 yards from the German trenches. Ten per cent. of the four companies were stationed down at Louvencourt. The night before the attack, at 9 p.m., they marched up to St. John's Road from Louvencourt, about 7 miles and arrived at St. John's Road about 1 a.m.

'They were brigaded with the 88th Brigade and our men were supposed to attack the third German trenches about 5,000 yards distant. The other two lines of defence, i.e. Nos. 1 and 2, were supposed to be attacked by the 86th and 87th Brigades. At 7.30 in the morning, the 86th and the 87th attacked, but failed in their objective, that is, they were supposed to clean out Nos. 1 and 2 of the German lines and occupy them themselves and consolidate their position, and then the Newfoundland Battalion would pass over them on to the third line of the German defence. The 86th and 87th however failed because of the concentration of the machine guns, and then the Newfoundland Battalion was ordered to reinforce the 86th and 87th. This they did. The order came from the Commander to the O.C. [officer commanding] Companies. It was explained to them fully what they had to do. They formed up and started in extended formation; A and B Companies leading, C and D Companies supporting platoons, forty paces between, and twenty-five paces between sections. All then marched with the hope of taking the No. 3 line of defence.

'This country, where the No. 1 line of defence was located, had been shelled for over a week by British artillery of all calibres. This is a distinctive work from the infantry, and had nothing to do with our soldiers. Between six and seven that morning, Saturday, July 1st, the most intense bombardment had been made by the British on this No. 1 line of defence.'Our men then started as if on parade, marching smartly towards their objective point. After passing through their own barbed wire defences they passed on over a grassy mound into a valley over a sunken road, up to a gentle slope towards the German trenches, or No. 1 line of the German defence. They reached there in about ten minutes. They had hardly got clear of their own trenches and their own barbed wire when they encountered the shot from the machine guns, the shrapnel and high explosives from the Germans. The guns seemed to be brought up on platforms out of the bowels of the earth. The week's shelling and especially the intensive shelling of that morning, did not seem in any way to have interfered with the preparedness of the Germans. Notwithstanding, however, this rain of shot from the machine guns, the shrapnel, and the high explosives, our troops moved on as if at manoeuvres, never faltering for a moment, although men and officers were falling all around. This went on until those who were left reached the first line of the enemy's trenches. It was then seen that the German position could not be taken until further preparations were made by the artillery. The men were then withdrawn. The Regiment went into action with 26 officers and 783 men, and the casualties after the battle were found to be:

| Killed - Officers | 15 |

| Killed - Other ranks | 95 |

| Wounded - Officers | 16 |

| Wounded - Other ranks | 479 |

| Unaccounted for - Officers | 1 |

| Unaccounted for - Other ranks | 114 |

| TOTAL |

720 |

'Fortunately, most of the wounds were caused by machine gun bullets and were not of a serious character. Many of the injured men have already rejoined the Regiment.'

End of first section of published account.

Army Commander's View

- Left top: Beaumont Hamel town (behind German lines)

- British/French armies to the left ; Germans to the right.

- Somme River flows east to west across the territory.

- British forces were north of the Somme; French south of the Somme.

- Left red line: Starting position, Battle of the Somme July 1, 1916.

- Far right broken red line: Final position at end of offensive November 1916.

- Maximum distance between the two lines is about 6 miles.

- Allied casualties (i.e. killed and wounded) about 620,000.

- German casualties about 660,000

* * *

Soldier's View

Walking across No Man's Land against established enemy positions in the Great War.

Zooming in on the Beaumont Hamel area.

Many Great War documentary film sequences were filmed by the photographer who detailed this map.

His silent films of "The Great Advance" were rushed into theatres across the Empire.

Sadly he included no sequences of British staff officers scratching their heads and shrugging their shoulders ... as this might have forced the Empire's politicians to question the negligent waste of its volunteer soldiers.

Only some of the complexity and irregularity of the trench systems can be seen.

|

The Essex Regiment was to join the Newfoundlanders, but it could not get forward in time.

The Newfoundland Regiment was the only formation in No Man's Land.

All German artillery, trench mortar, machine gun and rifle fire would have been focused on them.

The Germans were well dug in, on high ground, with reinforced concrete bunkers dug deep in the underlying chalk.

The German Army provided for the defensive safety of their soldiers.

When the barrage ended, the soldiers had plenty of time to emerge from their shelters and prepare ... to successfully defend their lines at 0730hr.

Beaumont Hamel, short version:

The Germans had stopped a large surprise advance ... after 90 minutes of successful German defence of their positions ... at approximately 0900hr, the Newfoundland Regiment was sent on a ten minute walk into the guns ... alone.

The Newfoundland Regiment was the only formation in No Man's Land.

All German artillery, trench mortar, machine gun and rifle fire would have been focused on them.

The Germans were well dug in, on high ground, with reinforced concrete bunkers dug deep in the underlying chalk.

The German Army provided for the defensive safety of their soldiers.

When the barrage ended, the soldiers had plenty of time to emerge from their shelters and prepare ... to successfully defend their lines at 0730hr.

Beaumont Hamel, short version:

The Germans had stopped a large surprise advance ... after 90 minutes of successful German defence of their positions ... at approximately 0900hr, the Newfoundland Regiment was sent on a ten minute walk into the guns ... alone.

|

| A trench mortar shell bursts near a barbed wire entanglement. |

Newfoundlanders first had to thread their way through the 'web' of their own wire.

The few who survived No Man's Land found the German barbed wire entanglement uncut by artillery.

The entire advance and efforts to cut the German wire were done in full view of German artillery and machine guns.

|

| A German machine gun crew ... a formidable defensive system. |

Left to right:

Belt feeder ; gun operator ; officer with field glasses to command fire ; maintenance help and spare gunner.

As long as one soldier remains unwounded, the gun will probably continue to fire.

With the Newfoundlanders (and the other advancing troops that day) commanded to walk across open fields ... neither success nor survival were likely.

Consider the defensive power of this one concealed crew as it traverses the gun across the battlefield.

|

How machine guns can sweep No Man's Land.

|

Machine gun tactics - like other killing methods - were evolving rapidly during the war.

Human ingenuity.

Published account continues.

'Brigadier General D.E. Cayley, commanding the 88th Infantry bears testimony to the gallant conduct of the First Newfoundland Regiment in the memorable battle as follows:88th In. Brig., British Army in France, July 18, 1916.Your excellency, - You will have already heard of the very great losses suffered by the Newfoundland Regiment in the attack on 1st July. Colonel Hadow tells me that he has already written to you describing the action.The 29th Division was put in against what was proved to be the strongest part of the German line, and, as it proved, impregnable to direct assault. Battalion after battalion was sent forward without any success. Finally, two battalions of my Brigade, the Newfoundland and another were ordered forward.I was in a position to observe the advance of the Newfoundland Regiment. Nothing could have been finer. In face of a devastating shell and machine gun fire, they advanced over our parapets, not a man faltering or hanging back. They literally went on till scarcely an officer or man was left unhit. Their casualty lists are a sufficient proof of this.It was a cruel fate, which in this first real attack, allowed them to be nearly destroyed, without the compensating satisfaction of having got at the enemy. Also, that the one unit in the field of a Colony which has made such sacrifices, should suffer such a fate, is indeed tragic. I cannot sufficiently express my admiration for their heroism nor my sorrow for their overwhelming losses, which admiration and sorrow will be shared by all in Newfoundland.I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant(Sgd) D.E. Cayley Brig General.

End of published account section

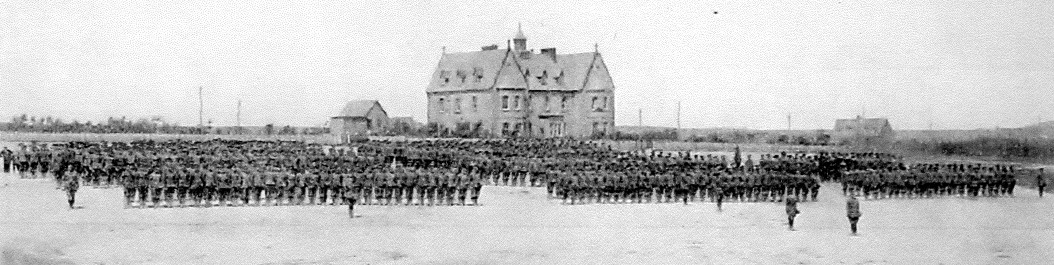

Less than two weeks after Beaumont Hamel more Newfoundlander volunteers are ready to 'do their part' ...

Inspection of Third Battalion, A and B Companies,

First Newfoundland Regiment before leaving for England on July 19, 1916.

In 1911 Newfoundland had a population of 242,000.

Published account continues

The grandest testimonial to our troops, however, came from the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Forces.

It was as follows: -

(No. 330. Telegram, received 9th July, 7.30 p.m.)

To Governor, Newfoundland :

Newfoundland may well feel proud of her sons. The heroism and devotion to duty they displayed on 1st July has never been surpassed. Please convey my deep sympathy and that of the whole of our armies in France in the loss of the brave officers and men who have fallen for the Empire, and our admiration for their heroic conduct. Their efforts contributed to our success, and their example will live.

Douglas Haig, Field Marshal.

...

'Private James McGrath briefly relates the story of Captain Windeler's bravery, and incidentally exhibits his own pluck and valour, as follows :

'I will never forget the beginning of the Somme offensive on July 1st, 1916. We advanced to the German trenches at 10 in the morning and the machine gun fire was something terrible. The Germans actually mowed us down like sheep. I managed to get to their barbed wire, where I got the first shot; then went to jump into their trench when I got the second in the leg. I lay in No Man's Land for fifteen hours, and then crawled a distance of a mile and a quarter. They fired on me again, this time fetching me in the left leg, and so I waited for another hour and moved again, only having the use of my left arm now. As I was doing splendidly, nearing our own trench they again fetched me, this time around the hip as I crawled on. I managed to get to our own line which I saw was evacuated as our artillery was playing heavily on their trenches. They retaliated and kept me in a hole for another hour. I was then rescued by Capt. Windeler who took me on his back to the dressing station a distance of two miles. Well, thank God my wounds are all flesh wounds and won't take long to heal up.'

End of published account

However, at night, as they tried to return to safety from uncaptured objectives, the same tin triangles assisted the work of the German snipers.

December 1916

The Newfoundland Regiment was given the rare title 'Royal' by King George V, as the result of an unrelieved two-week engagement in November-December 1917 in France, known as "Marcoing - Mesnieres". This location is a few miles southwest of Cambrai.

As losses increased, everywhere in the Empire there was increasing social pressure on 'slackers' ... those who had not volunteered ... to 'do their part'.

The notice above states: "It must not be said of us that the blood shed and treasure expended has been in vain"

Eventually, the Newfoundland government passed the Military Service Act on May 11, 1918 to provide for conscription.

'It was long realized that sufficient volunteers were not forthcoming to maintain the Regiment as a separate fighting unit, but it remained for our legislators to cast the one dark blot on the enviable military record of our Battalion, that of having to be taken out of the line because sufficient trained troops were not available to bring the Battalion up to fighting strength.'

Why should Beaumont Hamel be remembered ?

|

| Veterans after the War. |

The Newfoundland Regiment was a relatively small force compared to Britain's volunteer "New Army" of 500,000.

The Newfoundland Regiment's casualties at the Battle of the Somme were 720,

compared to the 6 month losses at The Somme on both sides of 1,280,000.

Was Newfoundland's tragedy a terrible waste ... a noble sacrifice ... of simply typical of the Great War ?

Can such a great loss from such a small community not be 'in vain' ?

Beaumont Hamel should be remembered because it is a simple story in a hopelessly complex human conflict.

The successes and failures of the humans in the story still evoke awe.